Utah Scientists Find Ancient Freshwater Under Great Salt Lake

Thousands of years of mountain snowmelt created a massive freshwater reservoir hidden beneath the Great Salt Lake's salty crust. This discovery could help prevent toxic dust storms while rewriting what we know about how water moves through the desert.

Scientists at the University of Utah just discovered something remarkable hiding in plain sight: a huge reservoir of fresh, drinkable water sitting right under one of the saltiest lakes in the world.

For thousands of years, snowmelt from Utah's mountains has been seeping underground and collecting in the spaces between sediments below the Great Salt Lake. This pressurized freshwater sits beneath a 30-foot layer of salt, and some of it may date back to the Ice Age when Lake Bonneville covered northwestern Utah 8,000 years ago.

The discovery happened because of something strange. As drought and water diversions dried up parts of Farmington Bay, odd circular mounds covered in reeds started appearing on the exposed lakebed. Professor Bill Johnson and graduate student Ebenezer Adomako-Mensah spent two years drilling wells into these mysterious round spots to figure out what was happening.

They found that pressurized freshwater was pushing up through natural pipes in the salt layer, creating the mounds. The bigger the mound, the fresher the water at its center. At the edges, the water turns salty again.

Johnson and his team are now mapping this hidden aquifer using instruments that measure water pressure, flow, age and chemical makeup. Their first published findings appeared in the Journal of Hydrology, with more papers on the way.

The Ripple Effect

This ancient water source probably won't refill the shrinking Great Salt Lake directly. The research shows that groundwater from the mountains reaches the lake mainly by seeping into rivers, not by flowing underground through the exposed playa.

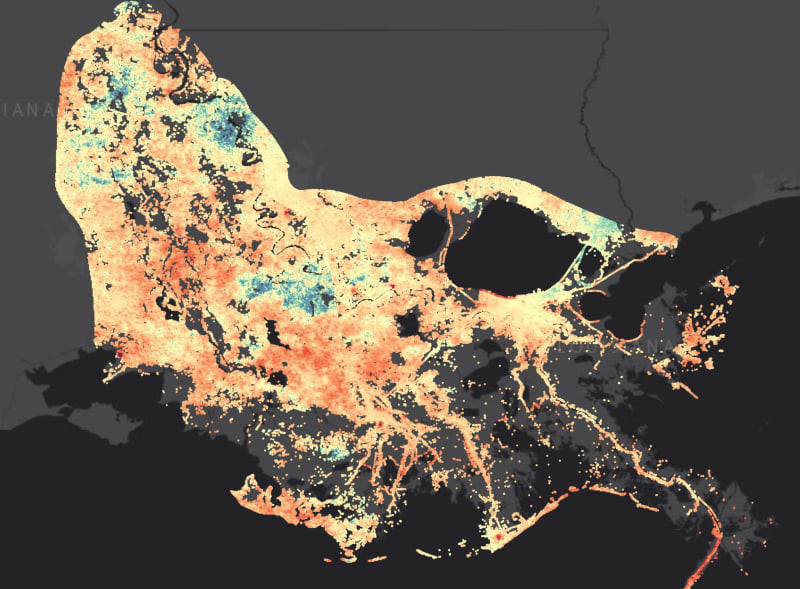

But Johnson sees another critical use. As the lake shrinks, exposed sediments create dangerous dust storms that blow toxic particles into cities along the Wasatch Front. The pressurized freshwater could flood high-elevation dusty areas to create protective crusts on the lakebed without depleting the aquifer.

The team is now checking whether they can use modest amounts of this water for dust control without weakening the upward pressure that keeps it flowing. They're also working to understand the full size and characteristics of this invisible lake beneath a lake.

What started as curiosity about weird mounds on a dry lakebed turned into a discovery that could protect public health while teaching scientists how desert water systems really work. Sometimes the most valuable resources are the ones we never knew existed.

More Images

Based on reporting by Phys.org

This story was written by BrightWire based on verified news reports.

Spread the positivity! 🌟

Share this good news with someone who needs it