JWST Finds Hidden Monster Black Hole in Early Universe

A galaxy named Virgil, seen just 800 million years after the Big Bang, appears normal in visible light but transforms into a cosmic powerhouse in infrared, revealing a supermassive black hole that challenges everything scientists thought they knew about how the universe grew up.

Scientists just discovered a galaxy playing cosmic hide and seek, and it's rewriting the rulebook on how black holes formed in the baby universe.

Meet Virgil, a galaxy that looks completely ordinary when viewed in visible light. But when University of Arizona astronomers pointed the James Webb Space Telescope's infrared camera at it, they found something shocking: a supermassive black hole so massive it shouldn't exist in a galaxy that young.

The galaxy sits 800 million years after the Big Bang, practically an infant in cosmic time. Yet its central black hole is already far larger than current theories say is possible.

"JWST has shown that our ideas about how supermassive black holes formed were pretty much completely wrong," said George Rieke, who leads the instrument team that made the discovery. "It looks like the black holes actually get ahead of the galaxies in a lot of cases."

For decades, astronomers believed galaxies formed first and slowly nurtured black holes at their centers, both growing together like dance partners. Virgil proves that's not always true. Sometimes the black hole races ahead.

The discovery happened because of what Virgil hides under thick blankets of cosmic dust. In visible wavelengths, it looks like any star-forming galaxy. But MIRI, the Mid-Infrared Instrument on JWST, sees through dust like an X-ray sees through skin.

"Virgil has two personalities," Rieke explained. "The UV and optical show its good side. But when MIRI data are added, Virgil transforms into the host of a heavily obscured supermassive black hole pouring out immense quantities of energy."

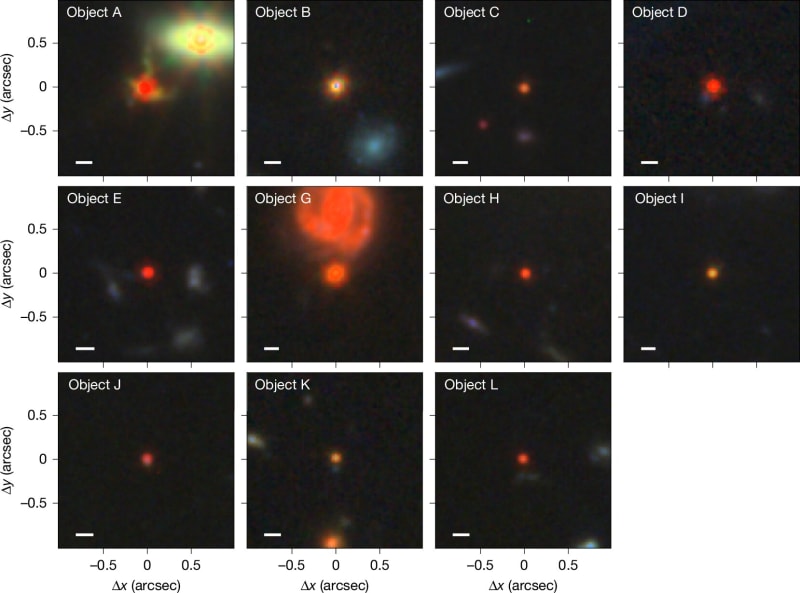

Virgil belongs to a mysterious group called Little Red Dots that appeared in huge numbers around 600 million years after the Big Bang, then mostly disappeared 1.5 billion years later. Scientists are still puzzling out what happened to them.

The Ripple Effect

This discovery means astronomers may be missing entire populations of hidden black holes throughout the early universe. Many telescope surveys take quick infrared snapshots but spend most observation time on visible wavelengths, potentially overlooking cosmic giants hiding in plain sight.

The finding also showcases University of Arizona technology lighting up the cosmic dark. MIRI can observe wavelengths invisible to human eyes, revealing phenomena that would otherwise stay hidden forever.

Understanding how black holes grew so massive so quickly helps explain how the modern universe took shape. These early cosmic monsters likely influenced how galaxies formed and evolved into the structures we see today.

For every cosmic mystery JWST solves, it reveals three more waiting to be discovered.

More Images

Based on reporting by Google: James Webb telescope

This story was written by BrightWire based on verified news reports.

Spread the positivity! 🌟

Share this good news with someone who needs it